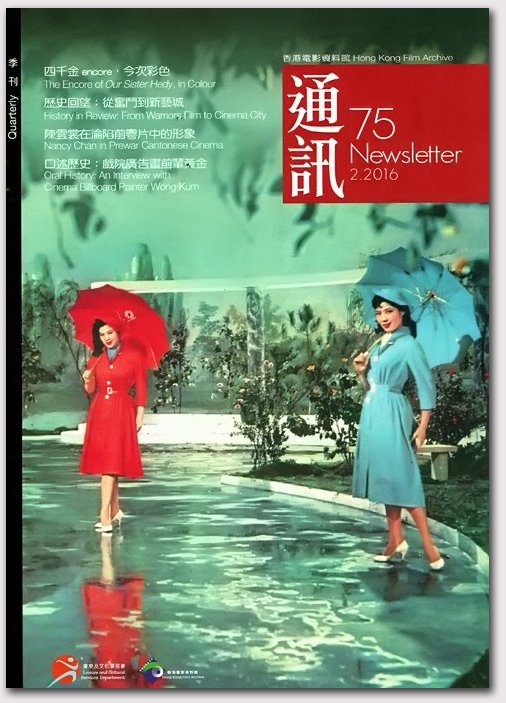

四千金 encore,今次彩色 2016 年 2 月 香港電影資料館《通訊》

得悉香港電影資料館快將放映《蘭閨風雲》(1959)和《龍翔鳳舞》(1959)確是喜出望外,這些年早已不再存寄望會看到這兩部陶秦在電懋﹝編按﹞時期拍的彩色片。無疑間中我們總會聽到在美國某唐人街某間舊戲院發現一些殘舊電影拷貝的消息,然後證實原來是某部一直以為遺失了的電影,失而復得確實是影迷最想聽到的新聞,但我從沒幻想這些「奇蹟」會發生在電懋「不見了」的電影身上。主要是我相信當年在陸運濤領導下,電懋有頗完善的行政制度,每部電影存運都應該有記錄在案,不會隨便丟放在某間戲院不理,但在2016年奇蹟竟發生了,而且是一口氣發掘出兩部當年的大製作。無綫電視曾在1980年深夜播映過一次《龍翔鳳舞》,即使畫面粗糙,也總算有 VHS 錄影流傳出來,而《蘭閨風雲》在1959年首映之後就真是一直芳蹤杳然,所以今次「出土」確是珍貴無比。

《蘭閨風雲》是《四千金》(1957)的續集,當年《四千金》拿下了亞洲影展最佳影片獎,令到想打造東方荷李活的陸運濤更加雄心萬丈,片中那種西式中產趣味,更成為電懋未來數年開拍的一連串時裝輕喜劇的基調。《蘭閨風雲》同樣是改編自鄭慧的流行小說,相比上集它是有其先天性的弱勢;在上集四姊妹雲英未嫁,內容圍繞她們情歸何處的戀愛、感情生活,自有叫人追看的吸引力,但到了《蘭閨風雲》四千金中三個已為人妻,剩下林翠其實也名花有主,步入教堂只是遲早問題,還有甚麼「故事」呢?大姐穆虹懷疑丈夫林蒼有外遇,結果原來只是生意上出現問題,虛驚一場;二姐葉楓開個人畫展,得蒙一神秘富豪賞識,委約她畫一幅大型油畫,要長時間留在淺水灣一間大宅完工,丈夫陳厚擔心她紅杏出牆,更想到用反間計假扮偷情,企圖引起葉楓妒忌;四妹蘇鳳當空中服務員的丈夫田青被公司派往外國長駐,她決定和丈夫同行;而任教師的三姐林翠一片善意,試圖改變她一名學生的父親喬宏偏執古怪性格,令到這單親家長產生傾慕之情 …… 都不外是茶杯裏的小風波,但卻又依然看得我津津入味。相信除了《四千金》真的叫人懷念,於是變奏也好,延續也好,怎都樂意追看下去,而且這次更是彩色!

事實上《蘭閨風雲》很多小節都刻意回應《四千金》,例如沿用了不少上集的配樂。開場不久林翠鬼馬地在葉楓跟前扮她在上集挑逗陳厚時跳 Cha Cha 的模樣,更哼了幾句當時唱機播的〈你跟我來〉;另外《四千金》林翠「左一劍右一劍」那場經典「劍舞」,在今集變成了在球場上球加上呼拉圈的步操舞 …… 陶秦勾劃他心目中那個理想的中產世界依然叫人嚮往,記得上集開場四姊妹先後去她們家附近的士多買煙斗送給父親作生日禮物,結果王元龍收到了四個煙斗。今次開場則先後見到四棵聖誕樹 —— 穆虹、葉楓、王元龍和林翠蘇鳳住的「祖家」,以及林翠未來家翁李允中的家 —— 形狀大小不同,但各人客廳均亮起一棵聖誕樹。起碼在陶秦的鏡頭下,五十多年前的香港可能比現時更西化呢。

小時候我是曾經在東樂戲院看過《蘭閨風雲》,已幾乎全無印象了,但腦海裡至今仍記得一場戲,是葉楓赤腳在酒吧枱面上隨著樂聲扭動身軀。這樣的畫面在1950年代可能真的太激了,帶給我的震撼歷久難忘,不過我的記憶中漏了那是個甚麼場所,是在一間夜總會內?今次重看终於找到答案,原來是葉楓陳厚的家,他們開聖誕派對,一眾賓客蜂湧把女主人抬上吧台,在歡呼聲中葉楓嫵媚地在吧枱面上「俯視眾生」翩翩起舞。家中客廳有一個酒吧,不是做夢吧!另外林翠未來家翁李允中的家,客廳看到全海景;他遣派他司機送一隻洋狗給林翠作禮物,那個司機是穿上整套制服 …… 這一切不正是長久以來一代又一代人憧憬的中產階級 dream house 以及海派的派頭?

看舊電影很多時意外收獲是重睹一些消失了的風光,《蘭閨風雲》林翠在操場教學生玩呼拉圈,遠處看到喇沙中學的舊校舍,另外片中出現的那些在跑馬地、西半山、九龍塘的街景如今已面目全非,只有九龍瑪利諾那座古堡式校舍仍屹立如昔。同時也看到當年香港街道車少人少,感覺上很空曠有更多呼吸的空間,有一場戲雷震駕著 MG 開蓬小跑車,鏡頭竟巧合拍到另一部開蓬車奔馳,相信以前的空氣一定是比現時清新得多了。

電影中的室內場面大部分是片場搭景,除了兩場飯店戲,一中一西都是取實景,難得給我們看到當年食肆的風貌,以前的酒樓飯店幾乎都沒有私人房間的設施,片中的中菜館看似是吃北方菜的,那些屏風間格年輕的觀眾大概都未見過了。另外那間西餐廳,附有舞池兼樂隊現場演奏,四千金一家團聚的那張長餐桌上擺放了一座冰雕,香檳酒杯是矮圓形那種而不是近年通用的窄長形。很多視覺上的細節其實都輕輕提醒我們,那確是一個逝去了的時代。

可能是我個人偏見,雖然陶秦在1959年過檔邵氏後拍的三部彩色歌舞片《千嬌百媚》(1961)、《花團錦簇》(1963)和《萬花迎春》(1964),論豪華、瑰麗、規模皆遠超出《龍翔鳳舞》,《藍與黑》(1966)更為他再度帶來亞洲影展最佳影片的榮譽,但我仍認為他在電懋那幾年的作品最具玩味,片種也變化多端,可惜很多已失傳。《驚魂記》(1956)單從劇照看,那些強烈的光影對比就很有四十年代荷里活 Film Noir(黑色電影)的風格。《童軍教練》(1959)沒有愛情線,獨靠梁醒波的喜劇才華撐起,片中一場營火會天才表演,童子軍扮貓王大唱樂與怒,才十歲左右的陳梁兩寶珠更合跳 Cha Cha 舞,試問除了電懋還有哪間電影公司會投資拍一部以童軍為題材的電影?《三星伴月》(1959)刁蠻任性的林黛,再婚後「亡夫」突然出現,後又結識了一新潮藝術家,一個已婚兩次的婦人周旋在三男之間,意識確是太前衛了,難怪當年的觀眾不接受。與同是林黛主演、由岳楓導演張愛玲編劇的《情場如戰場》(1957)比較,可以看到陶秦的「西化」是去到幾盡。《天長地久》(1959)恐怕也沒機會看了,劇照中葉楓陳厚王萊喬宏的配搭總使我聯想起 Douglas Sirk 的作品,而陶秦去了邵氏之後的確把Sirk最出名的催淚片《春風秋雨》(Imitation of Life)翻拍成《曉風殘月》(1960)。然而他在電懋拍的最後一部作品《蘭閨風雲》,和《四千金》、《龍翔鳳舞》一樣,將港式、海派和洋化三者作出完美融合,有一種令人窩心的溫柔敦厚,恰似五十年代姚莉唱的那些將英文歌翻成國語的「中詞西曲」,此種優閒精緻的味道去到六十年代已不復再了。

記得《四千金》中四姊妹在情場不過兜轉了一陣,好像不費吹灰之力,很從容就找到條件優秀的如意郎君。且看葉楓順著舞蹈節奏,隨意發個「怎你還不上?」的表情,再伸出食指撩兩撩,陳厚已乖乖就範。陶秦轉投邵氏不久拍的《皆大歡喜》(1961)電影資料館曾上映過,同樣又是四個女主角,為求達到目的,滿肚子計謀、策略,機關算盡,既狼且放,搶得就搶,完全不似另外那四位,只管沉醉在她們舒適安逸的世界。如果說六十年代香港社會開始急劇變化,節拍正好有如當時風行的扭腰舞般激烈,《蘭閨風雲》就仍是屬於五十年代的香港,仍是 Cha Cha 式的節奏,輕盈、俏皮、寫意,不徐不疾。兩部電影的情懷、心態各異除了是時代的改變,也許亦代表了電懋、邵氏兩派不同的經營哲學吧。

《蘭閨風雲》的結尾,父親王元龍得悉自己身患絕症,最後心願是親眼見到女兒林翠和未婚夫雷震共諧連理,電影最後一幕,病重的父親挽著女兒步入教堂把她託付給她未來的丈夫,本應屬喜氣洋洋的日子,眾人的心情皆無比沉重,四個多小時的輕喜劇想不到是在淡淡的哀傷氣氛中作結。

1959年公映的《蘭閨風雲》是陶秦送給電懋的最後一份禮物,或者也可以看成是一首惜別1950年代香港的輓歌。

編者按﹕

國際電影懋業有限公司(簡稱電懋)為新加坡國泰機構於1956年在港正式成立的電影製作公司。

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Encore of Our Sister Hedy, This Time in Colour

Englsih Translation by Vivian Leong

It is such a pleasant surprise to learn of the Hong Kong Film Archive’s screenings of Wedding Bells for Hedy (1959) and Calendar Girl (1959). Directed by Doe Ching during his tenure at MP&GI(1), I had not harboured any hopes of watching these colour titles(2) again for years. Every once in a while, we hear news about how some dilapidated copies of lost films are found in some old theatres in American Chinatowns. Certainly for cinephiles, such rare finds are welcome news. Yet, I have never expected this sort of miraculous fate would befall the long-buried MP&GI films. It is because MP&GI, under the leadership of Loke Wan Tho, had an organized system keeping records of the shipping and handling of their films, thus making it unlikely for their reels to be left sitting around in random theatres. One could only find a crude-looking copy of Calendar Girl on VHS that was produced from Television Broadcasts Limited’s (TVB) one-time late night broadcast in 1980. On the other hand, Wedding Bells for Hedy had proven to be elusive since its premiere in 1959. Therefore, the Hong Kong Film Archive’s recent screenings of these two big productions of yesteryear is a significant and valuable ‘unearthing’ of sorts.

Wedding Bells for Hedy is the sequel to Our Sister Hedy (1957). The latter scooped Best Film at the Asian Film Festival, which was then a great boost to Loke’s ambition to build a ‘Hollywood of the East’. The Westernized middle-class lifestyle depicted in the film set the tone for MP&GI’s subsequent urban comedies. Compared to the first film, the sequel —— also adapted from a popular novel by Cheng Wa —— is hampered by its inherent weakness. While the first installment entices viewers by revolving around the four bachelorettes’ pursuit of love, three of them are already married in the sequel. The remaining single girl, played by Jeanette Lin Tsui, is in a committed relationship by then, rendering her eventual marriage a matter of time. So what are the stories left to be told?

The elder sister, Mu Hong, doubts her husband’s fidelity but his woes turns out to be business-oriented. The second sister, Julie Yeh Feng, holds an art show and gains the interest of a secretive tycoon. He commissions her to paint a large oil painting, which requires her to spend long periods of time at a mansion in Repulse Bay. Her husband, played by Peter Chen Ho, suspects her of cheating. So he hatches up a plan to fake an affair in attempt to provoke his wife’s jealousy. Meanwhile, Dolly Soo Fung, the youngest sister, decides to go along with her husband, Tian Qing, a flight attendant whose company is sending him overseas. The third sister (Lin) is a teacher who is trying to transform her student’s eccentric father, played by Roy Chiao. Little does she know that her act of kindness will lead to the budding feelings between the widower and her. All these plotlines concern matters that seem to be rather frivolous yet I still find them thoroughly enjoyable. The wonderful Your Sister Hedy is so memorable that whether it is a variation or sequel, I am more than happy to keep watching. Not to mention this one is in colour!

One would notice Wedding Bells for Hedy deliberately echoes Our Sister Hedy in minute detail, such as adopting most of its original score. In the beginning of the sequel, Lin playfully mimics the cha-cha moves her elder sister used to flirt with her future husband in the last film. She even hums the song that is played during her sister’s scene. Also, Lin’s iconic ‘sword dance’ in the previous film has becomes a marching dance with a ball and a hula hoop. The middle-class utopia depicted by Doe remains enticing. In the earlier film, the sisters visit a nearby shop separately and each of them buys a smoking pipe as a birthday present for their father (played by Wong Yuen-lung), who ends up with four pipes. Then in the opening minutes of the sequel, four Christmas trees of different size and shape light up the respective living rooms of Mu’s home, Yeh’s home, the ancestral house where Wong lives with Lin and Soo, and the home of Lin’s to-be father-in-law, Li Yunzhong. Under Doe’s lens, Hong Kong of fifty-some years ago is perhaps more westernized than the city today.

As a kid, I watched Wedding Bells for Hedy at the Prince’s Theatre. I could recall not much of the film but the scene in which a barefoot Yeh dances on a bar table. An image like this was perhaps too outrageous for the 1950s and left me with a lasting impression. But I have forgotten where the scene is set. Was it inside a night club? I finally found the answer when I re-watched it this time. It is actually at the home of Yeh and Chen during a Christmas party. The cheering crowd carries the hostess onto the bar, where she teasingly dances to their applause. What a dream it is to have a bar in the living room! Moreover, look at the panoramic sea view at the home of Lin’s future father-in-law and his gift of a dog to Lin via delivery by a chauffeur dressed in full uniform. Are they not the bourgeoisie dream house and extravagance coveted by every generation?

The unexpected reward of watching old films is that they take you on a journey to certain vanished scenaries. A scene in Wedding Bells for Hedy where Lin is teaching her students to play hula-hoop shows the old campus of La Salle College far in the background. The street views of Happy Valley, the west side of the Mid-Levels and Kowloon Tong in the film look nothing like that anymore today. Only the castle-like campus of Maryknoll Convent School is still standing tall, just like yesterday. Meanwhile, one can tell that there was a lot less people and cars in the streets of Hong Kong, which seemed to have a lot more breathing room. In one scene, Kelly Lai Chen is driving in his MG convertible sports car when another convertible coincidentally enters the frame. I believe that the air back then must be fresher than today’s.

Most of the indoor scenes of Wedding Bells for Hedy were filmed in the studio except two restaurant scenes—one Chinese cuisine and the other Western—were shot on location, giving us a rare view to the ambiance of restaurants in that era. Private rooms were not common at the time, and the screens used in the northern Chinese cuisine restaurant may seem foreign to the young viewers today. The western restaurant has a dance floor and a live band. The four sisters and their family enjoy their reunion dinner at a long table decorated with an ice sculpture. Champagne is served in coupes instead of flutes that only became popular in recent years. The many visual details in the movie gently reminds us that was indeed a bygone era.

Doe jumped ship to Shaw Brothers in 1959 and directed Les Belles (1961), Love Parade (1963) and The Dancing Millionairess (1964), which all outshining Calender Girl in scale and spectacle. The Blue and the Black (1966) even won him Best Movie in Asia Film Festival. Still, perhaps due to my personal biases, I believe Doe displayed more playfulness and versatility during his tenure at MP&GI. Unfortunately, most of the titles during that period were long lost for good. Judging by its production stills, the strong lighting contrast of Surprise (1956) indicates a strong resemblance to the styles of 1940s Hollywood film noir. The Scout Master (1959) does not feature any romantic subplot and solely relies on the comedic talent of Leung Sing-po. During a campsite talent show in the film, the scouts impersonate Elvis Presley’s rock-and-roll performance while young Chan Po-chu and Leung Bo-chu—barely ten years old at the time—dance the cha-cha. Which company, besides MP&GI, would invest in a film about scouts?

In The More the Merrier (1959), a wayward Linda Lin Dai remarries only to find her ‘late husband’ returns unexpectedly. Then she finds herself involved with a fashionable artist. This story a woman twice married and surrounded by three suitors, was quite forward at the time. Hence the audiences’ disapproval was not much of a surprise. Compared to another film starring Lin, the Griffin Yueh Feng-directed and Eileen Chang-penned The Battle of Love (1957), one can see how deep-seated ‘westernization’ is in Doe’s films. The chance of watching The Tragedy of Love (1959) is also quite slim. Its star-studded cast, featuring Yeh, Chen, Wang Lai and Chiao, somehow reminds me of Douglas Sirk’s films. In fact, Doe adapted Sirk’s renowned tearjerker Imitation of Life (1960) into Twilight Hours (1960) for Shaw Brothers. That said, as his last MP&GI title, Wedding Bells for Hedy—just like Our Sister Hedy and Calendar Girl—combines the styles of Hong Kong, Shanghai and the West perfectly. It has to ability to warm one’s heart with its gentleness and sincerity, just like Yao Li’s Mandarin covers of English songs from the 1950s. However, such leisure and refinement would not reappear in the 1960s.

The four sisters in Our Sister Hedy only make a few short rounds in their quests for love and, looking rather effortlessly, find their ideal husbands with outstanding packages. Simply by dancing to the music and giving him the greenlight with a flirtatious look, Yeh has already twisted Chen around her finger. All the Best (1961), which Doe made not long after he joined Shaw Brothers, was previously screened by the Hong Kong Film Archive. It also depicts four women in pursuit of love. They are tactful, calculating and preying like a pack of wolves—a stark contrast to the earlier film’s quartet, who only care for indulging in their comfortable and carefree world. If the 1960s marked the beginning of Hong Kong’s rapid transformation, like the popular twist and shout of its time, then Wedding Bells for Hedy would belong to the 1950s, like the light-hearted, buoyant cha-cha. The sentiments and attitudes of the two films not only reflect the change of time but also the different philosophy of Shaw Brothers and MP&GI.

By the end of Wedding Bells for Hedy, the girls’ father (Wong) learns of his terminal illness and his final wish is to witness his daughter Jeanette Lin’s marriage to Kelly Lai. The wedding scene in the finale sees the ailing father walking the bride down the aisle. On this supposedly joyful occasion, everyone is stricken by a heavy heart. After four-plus hours of light comedy, the story ends on a surprisingly sad note.

Released in 1959, Wedding Bells for Hedy was Doe’s parting gift to MP&GI, or it can be seen as an elegy for 1950s Hong Kong

Editor’s note:

1. Motion Picture & General Investment Co Ltd (MP&GI) was a film production company in Hong Kong set up by the Cathay Organisation of Singapore in 1956.

2. Calendar Girls (1959) and Wedding Bells for Hedy (1959) were both acquired from the Cathay Organisation of Singapore in 2004.